Apollo

Investment Management

Considering oil palm plantations

In recent years I have paid little attention to the plantation sector, despite its importance

to several Southeast Asian economies and to the global food supply. The rapid expansion of

the sector has caused justifiable concern on deforestation (we now have very little rainforest

left), land acquisition (what happens to the former owners), the biodiversity lost to the

monoculture (what happens to the orangutans and other wildlife), and the direct environmental

damage (from fertilisers, pesticides, and peat burning). The industry is now often vilified,

but it will not be intentionally downsized - and since it is now by far the world's largest

source of edible oil, and yields far more oil per hectare than any other crop, we must

hope that biological threats never prove serious. Apollo Asia Fund has no investments in

plantations at present, but if I were considering them, or running a large

global fund that had to invest in the sector, I would wish to be

environmentally discriminating, and this is how I would begin to screen the companies.

- Invest only in members of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, RSPO

- check the list

here. Probably most listed companies are

members, but Astra Agro Lestari is one striking exception.

- Check that the company has been submitting its Annual Communications of

Progress

- supposedly mandatory, but Genting Plantations and Tradewind

Plantations are among those that have not.

- Check what the ACOPs say

- Boustead Plantations has only

4 of its 50 estates certified. QL Resources provides

none of the statistics requested and says its reasons for non-disclosure are confidential.

While scheduled to achieve 100% RSPO certification of its estates in 2015, it says it has

no plans for action to achieve this.

- Monitor the RSPO complaints board

- complaints, responses, and the status of investigations are publicly posted.

Equatorial Palm Oil is a joint venture partner and 20% associate of

Kuala Lumpur Kepong.

- Request thorough public disclosure of key statistics

- our list of recommended disclosures is below.

- Engage the companies directly, and ask questions

- especially on land acquisition and development, any labour and community grievances,

responses to climate change and to other challenges.

- Keep thinking

- additional criteria may be appropriate.

There seems to be a trend towards relying on certification by third parties, which is

understandable for customers and investors wishing to find simple solutions to complex

issues, but has some dangers. The scope of certification is often much more limited than

most readers realise. Some companies use RSPO and other organisations quite cynically,

to satisfy many questioners while deflecting attention from core issues. Golden

Agri-Resources for example publicizes sustainability efforts which are focused on its

existing pre-2010 estates, and diverts attention from the key issues relating to its

expansion and deforestation. It aims to get two minor end-products RSPO-certified, while

not disclosing its usage of non-certified CPO and palm kernel.

Its

ACOP is riddled with non-disclosures that make one wonder about the

company's commitment to the move towards sustainability.

Certifying organisations which are well intentioned at startup may be

rendered ineffective over time by new conflicts of interest, or bureaucratic

drift: new challenges may be inadequately taken into account. A reliance on

certification also sets up a vulnerability to corruption. The forestry sector

provides ample examples of the limitations of certification schemes.¹

For all these reasons, public disclosure and transparency are highly desirable. Reported

data may then be scrutinised, and new questions asked. Few companies currently report

adequately. Even if they did, an organisation like RSPO also has great value: it can bring

sector expertise to bear, and the eventual threat of sanctions or expulsion.

A three-pronged approach seems optimal for investors:

- information from RSPO, the most credible of the relevant organisations;

- strengthening RSPO criteria over time; and

- a push for increased public disclosure.

Our recommendations for minimum standard disclosures by forestry and plantation companies

were accompanied by some further discussion and detail when first published in January 2013

under the title 'Gaps in the canopy'. That list was as follows.²

Operational disclosures for plantation &

forestry companies

- recommended minimum

- on a consistent

basis, updated annually, tabulated with comparative data for prior years. |

| Landbank: |

| Name, location, size, licence (date obtained, years

remaining in lease or licence period) |

| Current status of all land held: concession / plantation / pending development / other |

| Breakdown of landbank by soil type and forest stocking (tree density) |

| Concessions: |

| Name, location, size, licence (date obtained, years

remaining) |

| Amount harvested from the concession |

| Harvesting permits |

| Estimated standing stock / density |

| Levies paid |

| Plantations (crop or forest): |

| Name, location, size, licence (date obtained, years

remaining) |

| Breakdown of area by terrain and soil-type |

| Net plantable area |

| Land area cleared in reporting period |

| Land clearing permits |

| Planting activity: hectares planted for each crop |

| Breakdown of stands by maturity³ |

| Area harvested |

| Realised harvest volume and yield |

| Levies paid |

| Log production: |

| Logs from selective harvesting |

| Logs from land clearing |

| Logs from plantations |

| Logs from other sources, with description |

Claire Barnes, 20 June 2014

with a great deal of help from Masya Spek

In 2010 Indonesia introduced its own Timber Assurance Legality

System (SVLK), a national alternative to the more stringent criteria of the Forest

Stewardship Council. The EU ratified a Voluntary Partnership Agreement (VPA)

based on this system in February 2014, but meanwhile SVLK standards have been

progressively watered down. In addition, there are many issues surrounding

implementation. Certificates have been issued to concessions involved in

court-convicted corruption, and independent monitoring bodies are not being

given the access needed to do their work. Data that should be in the public

domain are not. A scathing report issued by a coalition of NGOs highlights the

following shortcomings:

- Since its inception the SVLK standard was weakened repeatedly.

- SVLK certifies operations which are not in compliance with various

government regulations.

- SVLK certifies operations which are not sustainable.

- SVLK certifies operations which may source illegally and/or unsustainably

produced timber from other companies.

- SVLK certified companies had serious legality and sustainability issues

in their forestry operations

- Independent monitoring of the SVLK process has not been effective.

- and concludes that the system is ineffective in excluding timber

related to corrupt practices, natural forest clearance harming indigenous

communities and critically endangered species, peatland drainage and burning;

and that certified processed products like pulp or paper may have been

sourced from any type of illegal and/or unsustainable operation.

WWF's punchy press release is here;

the full report is entitled SVLK

flawed: an independent evaluation of Indonesia's timber legality certification

system'.

-

To save readers from overlooking data reported in different

places, information from the RSPO ACOP should be added, including the number of

strategic operating units certified, the number yet to be certified, and the date

by which this is to be achieved.

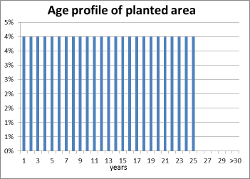

- The most helpful graphic display of the age profile for a plantation

group, and for each strategic operating unit of estates and mills, is the format shown

on the right. Shown here is an ideal steady-state plantation with a 25-year replanting

cycle. If there are years for which the percentage is significantly higher than 4%, the

implications for bunched replanting requirements and mill throughput variation

are apparent at a glance.

Previous reports:

- 18 Apr 14 World in flux:

1Q14 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 10 Jan 14 The next three

decades may be different: 4Q13 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 3 Oct 13 Overcomplexity

to dysfunctionality: 3Q13 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 7 Jul 13 Ominous tremours:

2Q13 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 6 Apr 13 Good governance

is vital: 1Q13 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 22 Jan 13 Gaps in the

canopy: suggestions for HSBC's forest policy

- 16 Jan 13 Markets

expensive, complacency dangerous: 4Q12 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 12 Oct 12 Cognitive

dissonance: 3Q12 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 16 Jul 12 The imprecision

of vital statistics: 2Q12 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 4 Apr 12 Nifty

valuations: 1Q12 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 8 Jan 12 The primacy

of resilience: 4Q11 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 16 Oct 11 Not a normal cycle:

3Q11 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 26 Jul 11 Open letter

to Securities Commission Malaysia: feedback on Corporate Governance Blueprint

2011

- 22 Jul 11 Bureaucracy and

overcomplexity: 2Q11 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 8 Apr 11 World in

upheaval: 1Q11 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 8 Jan 11 Unsustainable

growth: 4Q10 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 8 Oct 10 More bull:

3Q10 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 4 Jul 10 Real-world

turbulence, market lull: 2Q10 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 5 Apr 10 Limits to

growth: 1Q10 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 23 Mar 10 Energy for Asia:

an overview

- 11 Jan 10 Dangerous times:

4Q09 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 5 Oct 09 Vertigo again:

3Q09 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 6 Jul 09 A major bounce:

2Q09 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 7 Apr 09 Falling prices,

long-term value: 1Q09 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 6 Jan 09 Tortoise

still crawling: 4Q08 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 6 Oct 08 Crisis and

opportunity: 3Q08 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 7 Aug 08 Thai

dividend taxation and NVDRs

- 13 Jul 08 Tectonic shifts:

2Q08 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 10 Apr 08 The turn of the

stockpicker: 1Q08 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 11 Jan 08 More interesting

times: 4Q07 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 8 Oct 07 Complacency

and euphoria: 3Q07 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 6 Jul 07 The

fully-invested bear: 2Q07 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 13 Apr 07 The case for

long holidays: 1Q07 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 6 Jan 07 Thai-phoon

battered: 4Q06 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 6 Oct 06 Snakes and

ladders: 3Q06 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 5 Jul 06 To the top

and down: 2Q06 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 7 Apr 06 Climbing a wall

of irritations: 1Q06 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 7 Jan 06 Slower growth,

relative value: 4Q05 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 4 Oct 05 Liquidity

and haze: 3Q05 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 5 Jul 05 Calm before

the storm?: 2Q05 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 4 Apr 05 Limitations

in a growing investible universe: 1Q05 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 7 Jan 05 A time to

recognise good fortune: 4Q04 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 10 Oct 04 North-east

monsoon approaching: 3Q04 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 9 Oct 04 Accounting

& disclosure issues in Asia

- 6 Jul 04 Relative

calm: 2Q04 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 4 Apr 04 Risk

warnings still in force: 1Q04 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 7 Jan 04 Fun

while it lasts: 4Q03 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 4 Oct 03 Rise

extended: 3Q03 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 4 Jul 03 Apollo

in wonderland: 2Q03 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 6 Apr 03 Turbulent

times, but underlying growth continued: 1Q03 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 10 Mar 03 Pirates attempt

to seize whole Armada: pitfalls of investing in Malaysia

- 3 Jan 03 A new

high & cautious optimism: 4Q02 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 17 Oct 02 Relative

resilience: 3Q02 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 8 Jul 02 A good

harbour: 2Q02 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 4 Apr 02 Awash

with liquidity: 1Q02 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 4 Jan 02 Steady

as she goes: 4Q01 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 10 Oct 01 Resilience

in adversity: 3Q01 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 5 Jul 01 Prices

more volatile, value still compelling: 2Q01 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 3 May 01 Opportunities

for selective investors in Asia: article for the Gloom, Boom & Doom

Report

- 13 Apr 01 Earnings

yield 19%; some risk discounted: 1Q01 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 5 Jan 01 High

seas now evident - how we navigate: 4Q00 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 10 Oct 00 Tidal waves

forecast, two stocks revisited: 3Q00 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 6 Jul 00 Price

stagnation, sensational valuation: 2Q00 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 9 Apr 00 A Pacific

Century - if not for Cyberworks: 1Q00 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 9 Jan 00 Excellent

values for interesting times: 4Q99 report for Apollo Asia Fund

- 11 Dec 99 Angel of

mercy, or falling angel? Strange happenings at Quality HealthCare

- 14 Nov 99 Apollo Asia

Fund: key terms & summary of features (updated 21 Oct 02)

- 18 Oct 99 Interesting

times ahead! & hence, opportunity: 3Q99 report for the Apollo 001

Fund

- 16 Sep 99 Opacity,

the Asian way? Stock exchange responsibilities on disclosure

- 6 Sep 99 The

all-way case for Asian investment

- 5 Sep 99 Our

type of company - and our type of valuation. A two-stock comparison

- 5 Sep 99 UAF

& Euroclear: lessons and issues

- 4 Sep 99 More

on dollar cost averaging

- 27 Jul 99 After gains,

value persists: 2Q99 report for the Apollo 001 Fund

- 6 May 99 Portfolio

value: an update

- 30 Apr 99 Investment

grade markets, and the imperatives of the herd

- 18 Apr 99 Value, not

momentum: extracts of 1Q99 report for the Apollo 001 Fund

- 3 Mar 99 Perfidious

Thais

- 16 Jan 99 The benefits

of dollar cost averaging

- 16 Jan 99 How good

is the investment case for Asia now?

- 31 Dec 98 Extracts

of manager's 4Q98 report for the Apollo 001 Fund

- 27 Dec 98 Nuggets on

rereading my book, Asia's Investment Prophets